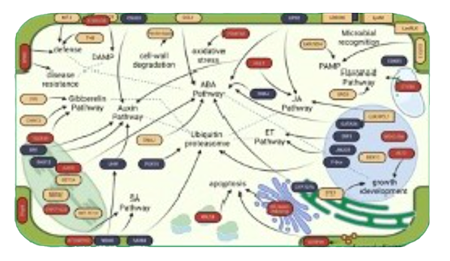

The goal of the Plant-Microbe Interfaces SFA is to gain a deeper understanding of the diversity and functioning of mutually beneficial interactions between plants and microbes in the rhizosphere. The plant-microbe interface is the boundary across which a plant senses, interacts with, and may alter its associated biotic and abiotic environments. Understanding the exchange of energy, information, and materials across the plant-microbe interface at diverse spatial and temporal scales is our ultimate objective. Our ongoing efforts focus on characterizing and interpreting such interfaces using systems comprising plants and microbes, in particular the poplar tree (Populus) and its microbial community in the context of favorable plant microbe interactions. We seek to define the relationships among these organisms in natural settings, dissect the molecular signals and gene-level responses of the organisms using natural and model systems, and interpret this information using advanced computational tools.

Importance of plant-microbe interfaces

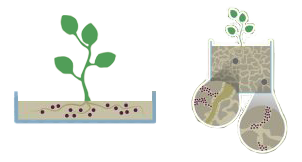

The beneficial association of plants and microbes exemplifies a complex, multiorganismal system that is shaped by the participating organisms and the environmental forces acting on them. Often these plant-microbe interactions can benefit plant productivity and performance by, for example, (1) affecting nutrient uptake and growth allocation, (2) influencing plant hormone signaling, (3) inducing catabolism of toxic compounds, and (4) conferring resistance to pathogens. In both natural and engineered systems, plants and microbes function collectively to determine the responses of terrestrial ecosystems to environmental changes as well as to offer potential as dedicated feedstocks for broader economic applications.

Importance of Populus

Populus, is a dominant perennial component of temperate forests and has the broadest geographic distribution of any North American tree genus. It has become the model woody perennial organism. Populus was chosen as the first tree genome to be sequenced, and an improved fundamental understanding of its interactions with microbes will enable the use of indigenous or engineered systems to address challenges as diverse as bioenergy production, environmental remediation, and carbon cycling and sequestration. Three interrelated scientific objectives create integrating themes for this SFA and drive needed advances in analytical and computational technologies.